Berkshire Theatre Group is proud to present the first musical in the nation to receive Actors’ Equity Association, municipal, and state approval: Godspell. Originally conceived in 1970 by John-Michael Tebelak when he was a student at Carnegie Mellon, Godspell was born of collaboration and a desire to spread a joyful message. With Tebelak’s vision and Stephen Schwartz’s music, Godspell quickly became a cultural phenomenon.

Godspell‘s Origin

Tebelak began writing Godspell for his Master’s thesis. According to Carol de Giere’s The Godspell Experience (2014), “his plan was to re-approach the Biblical parables and texts with the innocence of a child, and to play with the material as if it was a school recess” (de Giere 58). The first iteration was titled The Godspell and consisted solely of the text of The Gospels.

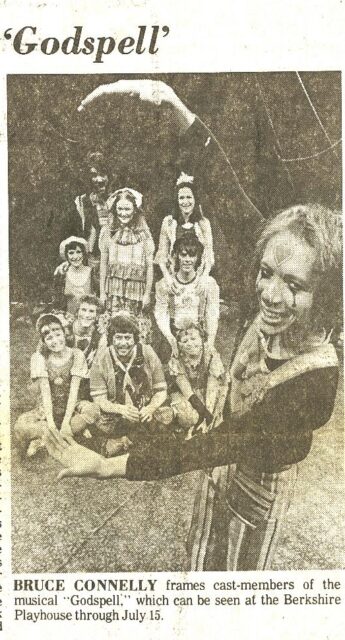

Image from a Berkshire Eagle review of Godspell at The Berkshire Playhouse from July 2, 1975.

The cast, clowns 1-10, were encouraged to experiment and play with the text—to make it their own and bring life to the words. This level of freedom and playfulness along with the vision and input from Tebelak truly transformed the text from discordant Bible parables into a play. With music written by a fellow student for pre-selected hymns, and a three-person band The Godspell premiered in December of 1970.

Godspell was given the chance at a New York City debut at La MaMa, an Off-Off-Broadway venue known for experimental theatre. Most of the original cast and some of the original creative team from Carnegie Mellon were able to reprise their roles. No formal script had been created after the Carnegie Mellon shows, and so a new round of experimentation, improvisation, and play commenced. The show was yet again a success. Producers Joseph Beruh and Edgar Lansbury saw the potential in the piece and quickly signed on. Shortly thereafter, everyone began preparing Godspell for a move to The Cherry Lane Theatre. In order to transform this experimental work, new music was a must.

Stephen Schwartz, a fellow Carnegie Mellon graduate, was asked to join the team and compose a new score for the show in just five weeks. With an eclectic mix of styles and transitioning of longer monologues into music, Godspell began to transform into its final state. In 1971 it opened to rave reviews. It transferred to the Promenade Theatre and ran for over 2,000 performances. The first Broadway production of Godspell opened in 1976 at the Broadhurst Theatre. Throughout the 1970s, touring and international productions emerged from London and Toronto to smaller regional theatres such as Berkshire Theatre. Godspell’s cultural importance was undeniable.

Cultural Impact

The creation of Godspell was driven by young artists—college students—who had grown up in the midst of the cultural revolution of the 1960s. Influenced by The Civil Rights Movement, the second wave of feminism, the sexual revolution, and the development of new countercultures aimed at questioning authority and fighting for freedom, Godspell was radical.

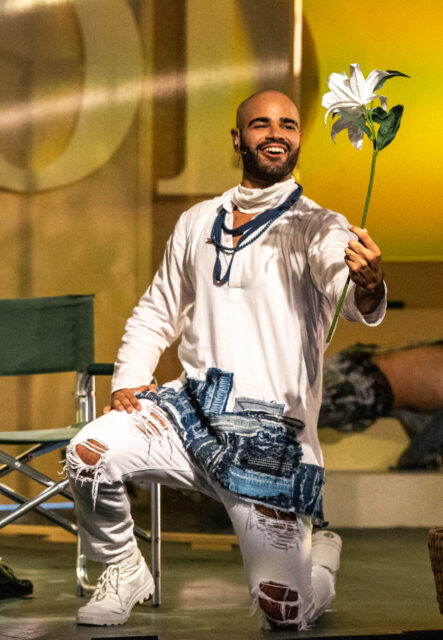

Nicholas Edwards in BTG’s Godspell, 2020. Photo by Emma K. Rothenberg-Ware.

Godspell revisits the idea of Jesus as a revolutionary figure. One who challenged authority and preached a new, radical message to the world: “love your enemies and pray for your persecutors.” Tebelak in a 1975 interview with Dramatics magazine stated that he, “wanted to make [Godspell] the simple, joyful message that I felt the first time I read [The Gospels] and recreate the sense of community.” Godspell was written in reaction to the world and to those in authority who saw a young Tebelak, in his “hippie” attire, leaving a church and assumed he had snuck in to loiter rather than to listen.

One of the most brilliant aspects of Godspell is its ability to be relevant to any time or place in which it is staged. The original cast were named only as clowns, which afforded them a level of theatrical freedom and honesty. Using clowns and comedy also afforded a degree of innocence, playfulness, and humor to the story that is essential to the balance of the show. As the show evolved, the characters were named after the actors who originated them, with the exception of Jesus and Judas/John the Baptist. This helped to illustrate the importance of bringing something of the self to each individual “clown.” As the show moves onward, each individual begins to join in to the community through song.

As productions began to spread across the country and the globe, it was imperative that a member of the original New York cast was there to help maintain the spirit and essence of the show. For Berkshire Theatre’s 1975 production, Howard L. Sponseller, Jr. came aboard as an alternate cast member and spokesperson for the spirit of the production. Sponseller was a classmate of Tebelak and performed in New York as well as overseeing the Toronto production in 1972.

Godspell, 2020. Photo by Emma K. Rothenberg-Ware.

Godspell was a hit in large part because it showcased the voices of a new generation. “It was a time when the so-called ‘generation gap’ caused confusion and lack of trust between young people and older adults” (de Giere 263). Today, the generation gap that exists is more extreme than ever, with the next generation—Generation Z—set to be the most ethnically and racially diverse in the nation’s history. When the show was revived in 2011, one of the main reasons cited for the revival was the divisive climate in the nation. The ability of Godspell to profoundly impact audiences has only grown throughout the years. What better way to address the divide amongst the population than with a musical about love, community, and connection?

Godspell Today

Berkshire Theatre Group’s production of Godspell is set now, in the world of Coronavirus. “Godspell got the green light after establishing a strict protocol to protect the health and safety of the audience, the performers and others involved in the show. We have been working daily and in the true spirit of care and collaboration with Actors’ Equity Association for the past several weeks” states Kate Maguire, Artistic Director and CEO. Since rehearsals began, new challenges and guidelines have arisen. Luckily, Godspell was built on innovation and creativity. The cast and creative team have added more safety measures, restaged, redesigned, and reimagined the show as each new situation demanded.

Kimberly Immanuel in BTG’s Godspell, 2020. Photo by Emma K. Rothenberg-Ware.

As with the original production, the act of creative collaboration and problem solving reinforces the community-building that is at the heart of Godspell. “Getting the chance to get up on stage and look at audience members in the eye and tell them this story, which is about people who are in isolation and turmoil coming together and building something beautiful by the end of the show is an experience that I will never forget for the rest of my life,” states Kimberly Immanuel, one of the disciples in BTG’s production of Godspell.

We are in the midst of a Global Pandemic. We are also in the midst of another cultural revolution. We are social distancing and maintaining physical space for the safety of all, which in turn can lead to feelings of isolation. We are also facing uncomfortable truths about the inequalities that have always existed in our society. The world is changing and evolving day by day, hour by hour, and minute by minute. So too does each note and each word of Godspell evolve and take on new meaning with every performance. In an era of uncertainty and isolation, Godspell’s message of hope and unity has never been more relevant.