By: Scout Swonger (They/Them/Theirs)

While vampires typically have their time in the spotlight (certainly not the sunlight) during Spooktober or in Twilight-related fan circles, Dracula has persisted as an evergreen classic in part due to its many themes ripe for deep mining and discussion.

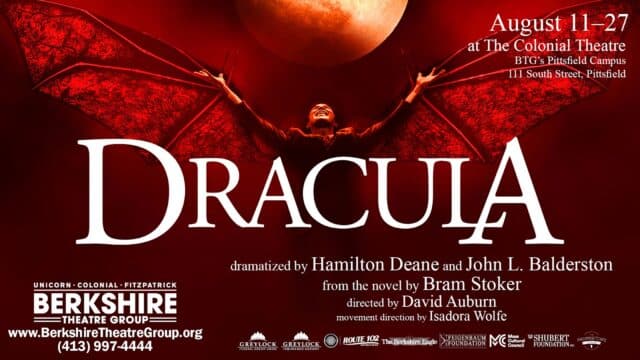

We are excited to spend some time traveling to Transylvania ourselves to explore these many nuances with audiences amidst David Auburn’s fantastical production of Bram Stoker’s classic dramatized by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston.

We are excited to spend some time traveling to Transylvania ourselves to explore these many nuances with audiences amidst David Auburn’s fantastical production of Bram Stoker’s classic dramatized by Hamilton Deane and John L. Balderston.

When thinking about the various undertones present in Dracula — and those vampiric works it has inspired since — an essential lens to view it through is queerness. While the aforementioned modern pop-vampiric work is popular for its iconic heterosexual romances, there has been a long and strong history of vampirism and the homoerotic lense being intrinsically entwined. In today’s blog, I’d like to showcase these interpretations of the work and give us another layer to consider when attending the current production at the Colonial!

Such interpretation must begin and is strengthened by the queer influences in Stoker’s own life. While Stoker did have a heterosexual marriage with his wife Florence, the few photos of the couple together and generally cool communication between the two provide evidence of a marriage with little if any romance. Stoker was more interested in his work, collaborations and friendships with other luminaries of the day, such as Oscar Wilde. Notably, Wilde (a former partner of Florence) was put on trial for gross indecency because of his homosexuality and sentenced to a criminal labor camp as homosexuality was a criminal offense in England at the time (homosexual activity was not made legal in England until 1967). This theory regarding Stoker’s own sexuality is further supported by the letters from his other male friendships, some containing extremely effusive language not typically used in purely platonic relationships. A particularly striking example is found in a gushing letter to Walt Whitman, replete with a mix of professional as well as possible personal and even romantic adoration. This was followed by a specific physical description of himself, writing something of a long-form Tinder bio to draw Whitman into a closer relationship.

“You have shaken off the shackles and your wings are free. I have the shackles on my shoulders still—but I have no wings.” –Bram Stoker

The strongest example of queer themes in Dracula, however, is found in the text itself. It is important to remember first and foremost the period in which it was written and set. The Victorian era saw the beginnings of shifting social roles, particularly for women, amidst a culture of repression. As with any movement for social change, there was an intense social backlash that sought to suppress it and maintain the status quo. While the “New Woman” was fighting for liberation, women found themselves met with even greater pressure to adhere to the tenets of modesty, purity and docility that were expected. As British society saw an influx of immigrants from across the world, xenophobic ideology gained a greater platform. And as sex and sexuality entered a more public sphere of discussion, such attempts to normalize those topics and practices within them seen as deviant saw a great deal of backlash. Generally, “The Other,” which was classified as any individual outside the rigid bounds of straight, white, male and protestant, found an increased presence in the zeitgeist. Any individual who fulfilled that classification was subject to persecution.

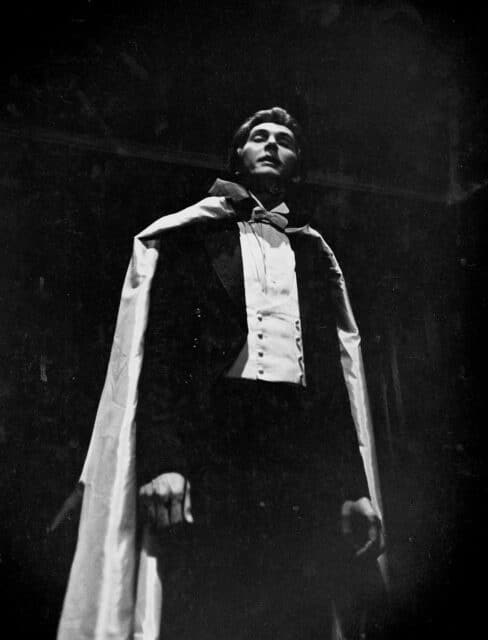

In Dracula, the titular character represents this “Other” in ways both literal and metaphorical. He is not only a vampire intruding on the world of humanity, but also an eastern European moving to British society and, most notably for our purposes, a man with an unabashed thirst for blood from any and all sexes. He seeks not partnership or romance, but a carnal connection. In this way, the character of Dracula embodies the desire that was so taboo to recognize in society at the time. This alone gives fodder for a queer reading of the text, as queer identities are often associated with hypersexuality in attempts to demonize. But Dracula not only embodies general physical desire but a desire to penetrate his victims and ingest their blood. This speaks not only to an unabashed and intense sexual nature but domination that is queer in its optics. These optics are present both in the instances when it is a male/male transaction, but also with female vampires who inhabit a dominant position over their male victims, bending the gender rules of the time. And in female/female vampiric transactions they provide another example of overtly queer interactions.

Once the queerness in the act itself is seen, we can also see how queerness was seen by society, further strengthening the allegory. Dracula, the symbol of pansexual desire, is a monstrosity that our central group of heroes —“the crew of light”— are on a mission to defeat. This group of upstanding, strong, straight British men, exemplary of society’s ideal, are not only defending their “helpless women” for whom vampirification by Dracula would ironically bring new strength and freedom for self-determination that their place in society as human women would not allow them, but they are defending themselves and their masculinity from possible castration and loss of virility. The crew’s quest to banish Dracula is both in their self-interest to maintain their humanity both as literal humans, but also as the kind of human men that are allotted the dignity of humanity that queer life is often not allotted.

Beyond purely homosexual interpretations, vampires inhabit a queer existence in a broader sense. Just as queerness can help describe a way of being that is in general opposition to the proscribed narratives of society and put a unifying label to identities that exist in a more liminal space, vampires exist in a space somewhere between humanity and creaturedom, as well as masculinity and femininity, and homo and heterosexuality. They inhabit a body that generally presents as human, and it is the departures from that – the hairy palms (another reference to the monstrous sexual activity), sharp teeth, pointed ears, and pale skin- which cause a sense of horror and disgust before even encountering the act that defines vampirism. And it is such abnormalities that the vampire is forced to conceal in their day-to-day life so they may stay discrete and carry out their desires at night. Similarly, it is common for those of the queer community to have to engage in efforts to “pass” —such as a gay man trying to pass as straight by masking mannerisms historically seen as feminine, or a trans individual seeking to pass as cis to avoid harassment— both in efforts to avoid abuse, harrasment, and discrimination. And it is at night in accepting enclaves where those mannerisms and ways of being that would be clocked as queer by the general public may simply be inhabited without shame or concern.

Yet possibly most striking in this modern queer reading is the blood connection. While certainly not purposeful at the time of Dracula’s writing or the conception of vampires, it is now hard not to find the undertones of HIV/AIDs fears in Dracula’s blood-lust. Beyond fears of the act of penetration itself, the horror is heightened by the blood transfusion so intimately enacted. With this modern lens applied, one sees not only the crew’s fears of becoming submissive, othered, and a creature of taboo carnal desire, but the metaphorical fear of disease and bodily destruction.

Dracula has given fruit for reflection on the state of society and identity in a variety of ways over the years. It is a piece that has stood the test of time both for its ability to capture the unique space that existed in society at the time of inception, as well as its ability to reflect the issues of the moment. This timeless story of the fight against the other can be seen not only as a heroic quest to defeat true evil but just as much an ardent fight to maintain the status quo and banish forces that question it. And at this moment where the queer community is under renewed attack and attempts at demonization, it is only natural to apply a queer lens to the work as we experience it an a new, fantastical light on The Colonial Stage.

This is only one of many readings of Dracula that enhance the already rich material. What comparisons to today or glimpses of insight into the past will strike you? I hope you will join us to find out!

References:

Künnecke, Lucas. “Blood, Sex and Vampirism: Queer Desires in Stoker’s Dracula and Le Fanu’s Carmilla.” Academia, 7 May 2015, https://www.academia.edu/12280616/Blood_Sex_and_Vampirism_Queer_Desires_in_Stoker_s_Dracula_and_Le_Fanu_s_Carmilla.

Xavier Aldana Reyes, ‘Dracula Queered’, in The Cambridge Companion to Dracula, ed. by Roger Luckhurst (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 125–35.

Lovett, Jessica. “” DANGEROUS DEVIATIONS”: QUEER VAMPIRISM AND AESTHETIC OTHERINGS IN STOKER’S DRACULA.”

Lavigne, Carlen. “Sex, Blood and (Un) Death: The Queer Vampire and HIV.” Journal of Dracula Studies 6.1 (2004): 4

Biography.com Editors. “Bram Stoker.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 5 Aug. 2020, https://www.biography.com/writer/bram-stoker.