American singer, songwriter, musical arranger and civil rights activist

Dramaturgical Research by Elaine Stoughton Cox

Eunice Kathleen Waymon (February 21, 1933–April 21, 2003), known professionally as Nina Simone, was an American singer, songwriter, musician, arranger and civil rights activist. Her music spanned a broad range of musical styles including classical, jazz, blues, folk, R&B, gospel and pop.

The sixth of eight children born to a poor family in Tryon, North Carolina, Simone initially aspired to be a concert pianist. With the help of a few supporters in her hometown, she enrolled in the Juilliard School of Music in New York City. She then applied for a scholarship to study at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia, where she was denied admission despite a well-received audition, which she attributed to racism (note that out of the 72 applicants in 1950, only 3 were accepted). In 2003, just days before her death, the Institute awarded her an honorary degree.

For an extensive bio and timeline: https://www.ninasimone.com/

Nina Simone as an Activist

Simone was close friends with Black playwright Lorraine Hansberry. Simone stated that during her conversations with Hansberry, “We never talked about men or clothes. It was always Marx, Lenin and revolution– real girls’ talk.” The influence of Hansberry planted the seed for the provocative social commentary that became the standard of Simone’s repertoire. One of Nina’s more hopeful activism anthems, “To Be Young, Gifted and Black,” was written with collaborator Weldon Irvine in the years following the playwright’s passing, acquiring the title of one of Hansberry’s unpublished plays. Simone was also friends with notable leftists such as James Baldwin, Stokely Carmichael and Langston Hughes: the lyrics of her song “Backlash Blues” were written by the latter.

Read more: “The Radical Politics of Nina Simone”

The United States In 1963

58 years ago, much of the news in the United States was dominated by the actions of Civil Rights Activists and those who opposed them. America’s role in Vietnam was steadily growing, along with the costs of that involvement. The Beatles were steadily rising in popularity, and President John F. Kennedy traveled to West Berlin to deliver his famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech. For the first time, the push-button was introduced. In 1963, the population of the world was 3.2 billion, less than half of what it is today. The final months of 1963 were punctuated by one of the most tragic events in American history, the assassination of President Kennedy in Dallas, Texas.

Major Events In The United States In 1963

- January 14–George Wallace is sworn in as governor of Alabama. In his inaugural speech he proclaims, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever.”

- February 19–Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique is released, slowly reawakening the Women’s Movement.

- April 16–Martin Luther King Jr. writes his Letter from a Birmingham Jail.

- June 11–JFK delivers a historic Civil Rights Address, in which he promises a Civil Rights Bill, and asks for “the kind of equality treatment that we would want for ourselves.”

- June 12–Medgar Evans is assassinated in Mississippi.

- August 28–Martin Luther King Jr. gives his “I Have a Dream” speech on the steps of the Lincoln Monument to at least 250,000 people.

- October 8–Sam Cooke and his band are arrested after trying to register at a “whites only” motel in Louisiana. In the months following, he recorded “A Change Is Gonna Come.”

- November 22–President John F. Kennedy is assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas, Texas.

- November 22–President John F. Kennedy is assassinated by Lee Harvey Oswald in Dallas, Texas.

September 15, 1963: The 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing

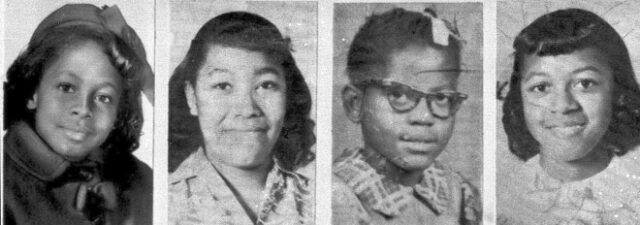

The four victims: Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, Addie Mae Collins and Cynthia Wesley

“…one of the most vicious and tragic crimes ever perpetrated against humanity” – Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Throughout the Civil Rights Movement, Birmingham, Alabama was a major site of protests, marches and sit-ins that were often met with police brutality and violence from white citizens. In fact, homemade bombs planted in homes and churches became so commonplace that the city was offhandedly known as “Bombingham.” Between 1947 and 1965, white supremacists planted more than 50 devices targeting Black churches, Black leaders, Jews and Catholics.

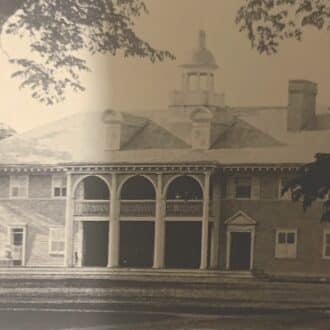

Throughout the first half of the 20th Century, the 16th Street Baptist Church hosted many meetings led by Civil Rights activists and other notable individuals like W.E.B. Du Bois, Mary McLeod Berthune, Paul Robeson and Ralph Bunche. In an effort to intimidate demonstrators, white supremacist members of the KKK routinely telephoned the church with bomb threats intended to disrupt these meetings, as well as regular church services.

A note of importance—violence on Black churches was not exclusive to the Civil Rights Era. The unthinkable horror of September 15, 1963 followed a long history of terrorism against Black houses of worship—a history as old as the United States. At approximately 10:22am, on Sunday, September 15, 1963, an anonymous man phoned the 16th Street Baptist Church. The call was answered by the church secretary Carolyn Maull. The anonymous caller simply said the words, “three minutes” to Maull before terminating the call. A few moments later, a bomb made of 19 sticks (some reports say “at least 15 sticks”) of dynamite detonated. They had been planted under the church steps the night before.

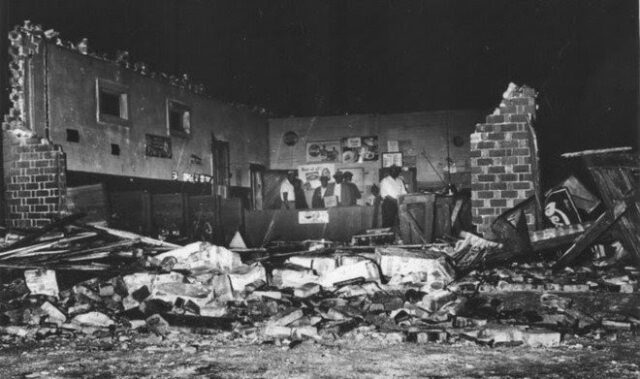

The bomb exploded on the east side of the building, where five young girls were getting ready for church in a basement restroom. The explosion sprayed mortar and bricks from the front of the building, caved in walls and filled the interior with smoke. Horrified parishioners quickly evacuated. It destroyed cars on the street outside and blew out glass windows nearly 100 feet away.

Beneath piles of debris in the church basement, the bodies of four girls were found. They were Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley and Carole Robertson, all age 14, and Denise McNair, age 11. A fifth girl who had been with them, Sarah Collins (the younger sister of Addie Mae Collins), lost her right eye in the explosion. Dozens of other people were injured (reports are unclear, but most say at least 20).

In the aftermath, violence escalated in Birmingham and across the country. Sadly, two more Black children were murdered that same night, as Birmingham rocked on the edge of white anarchy. A policeman killed Johnny Robinson, 16, with a bullet to the back, and two white teenagers shot and killed bicyclist Virgil Ware, 13. Several Black-owned businesses were fire-bombed. In response to the church bombing, described by the Mayor of Birmingham, as “just sickening.” The Attorney General dispatched 25 FBI agents, including explosives experts, to Birmingham to conduct a thorough forensic investigation. Many Civil Rights activists blamed George Wallace, Governor of Alabama and an outspoken segregationist, for creating the climate that had led to the killings. One week before the bombing, Wallace granted an interview with The New York Times, in which he said he believed Alabama needed a “few first-class funerals” to stop racial integration.

The city of Birmingham initially offered a $52,000 reward for the arrest of the bombers. Governor Wallace offered an additional $5,000 on behalf of the state of Alabama. Although this donation was accepted, Martin Luther King Jr. sent him a message stating, “The blood of four little children…is on your hands. Your irresponsible and misguided actions have created in Birmingham and Alabama the atmosphere that has induced continued violence and now murder.”

So, who did it?

There was little doubt as to who was behind the violence. A local Ku Klux Klan chapter, Klavern 13 was notorious for its acts of violence and terror. Nearly 50 explosives had been planted or tossed in racially motivated attacks over the previous 15 years. Most of the violence was against Black families that dared to move west of Center St., the city’s longstanding color line, or the white families that sold to them. As early as 1964, three men were identified by the FBI for their role in the bombing: Thomas Blanton, Jr. Bobby Cherry, and Robert “Dynamite Bob” Chambliss.

On May 13, 1965, a memorandum to FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover concluded that “the bombing was the handiwork of former Klansmen Robert E. Chambliss, Bobby Frank Cherry, Herman Frank Cash and Thomas E. Blanton, Jr.” FBI informants in the KKK said the four men went to the church that night to plant the bomb. Yet justice for the crime was a long time coming. No one was tried or jailed for the church bombing until 1977, when Robert Chambliss was tried and convicted. (He died in prison in 1985). Meaningful prosecution was prevented at many levels of local and federal government—all the way up to FBI Director Hoover. In 2000, Thomas Blanton and Bobby Cherry turned themselves in.

Recommended documentaries about Nina Simone and the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing:

What Happened, Miss Simone?

4 Little Girls

Summer of Soul

Now Playing at The Unicorn Theatre:

by Christina Ham

directed and choreographed by Gerry McIntyre

music direction by Danté Harrell

scenic design by Randall Parsons

costume design by Sarafina Bush

lighting design by Matthew E. Adelson

sound design by Kaique DeSouza

stage-managed by Jason Weixelman

Previews: Friday, August 13 at 7pm

Press Night/Opening: Saturday, August 14 at 7pm

Closing: Sunday, September 5 at 2pm

Tickets: Preview: $50

Tickets: $75

Proof of COVID-19 vaccination is required for this performance. Masks are mandatory for all patrons regardless of age (unless eating or drinking in specified areas).